Innovations driven by the world of disability

Far from stifling creativity, accessibility has been the source of inventions and products that today meet the needs of everyone

Monday, April 3, 2023

We live in a world of technologies, many of which were originally designed to compensate for disabilities, and some of which were developed by people with disabilities. Their uses have rapidly spread beyond their initial sphere to conquer the general public.

Here is a slice of life that is by no means universal, but in which everyone will no doubt recognise a moment in their daily lives. To write this article, I used tools so common that at first sight it would seem pointless to list them: a keyboard to put down on paper my ideas, several emails to discuss them with a few specialists, a phone call to check a source before leaving the office.

On the evening of this almost ordinary day, many people on the train are pulling out their smartphones. The sometimes lively atmosphere of the evening trains discourages some of them from taking out their headphones, so they watch their video with the sound turned off, and from time to time I glance over at my neighbour's screen where the automatically generated captions reproduce quite faithfully the lecture given by Jean-Marc Jancovici on energy and climate issues.

As I left the station, in the calm that has returned, the first pages of Couleurs de l'incendie accompany me. Pierre Lemaitre himself reads his own text, and the audiobook punctuates the end of my day, before I distract myself by listening to the film reviews on the Masque et la plume podcast in (very) fast-forward mode.

At the dinner table, everyone shares selected moments from their day and offers their best anecdotes. Little by little, the children become less small: it's no longer even necessary to remind them of a few basic hygiene rules - with the electric toothbrush, it's become fun.

At last everyone is asleep... or almost. I can hear my young teenager, headphones on, repeating: "next", "next", I deduce that he gives each track in his "discovery" music playlist little chance of being appreciated. And for tomorrow, shirt or jumper? Siri tells me the weather is summery, with showers expected.

From morning to night, I use tools that simplify my life, help me in my professional tasks, make my journeys smoother... I've adopted tools designed for people with disabilities, sometimes designed by them.

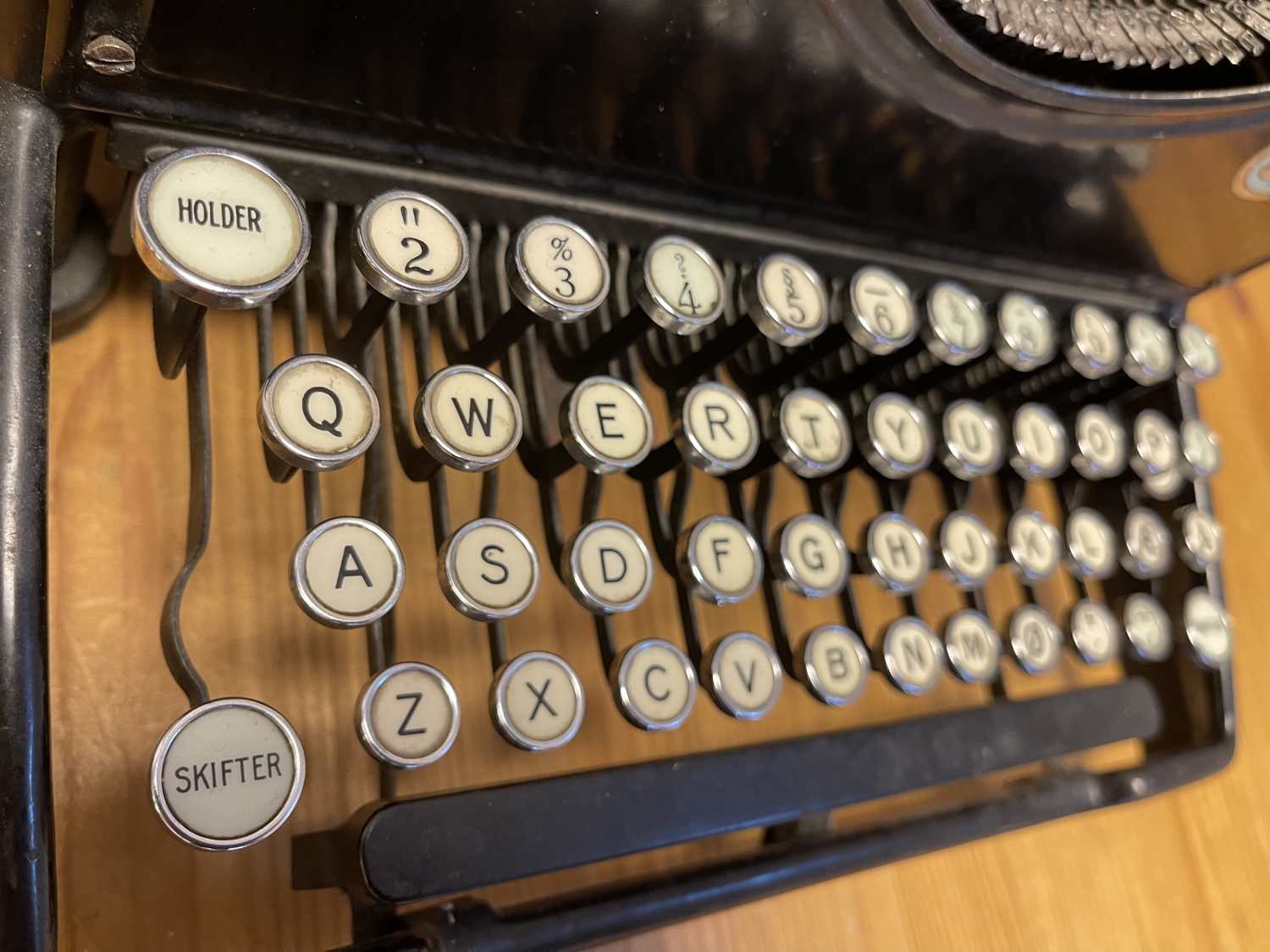

Who invented the keyboard? Christopher Sholes, Carlos Glidden and Samuel Soule are regularly cited as the designers of the QWERTY keyboard. This was at the end of the 19th century, and their typewriter was marketed a few years later by Remington.

However, this story glosses over the invention of Pierre Foucault, a French inventor who became blind at a very young age. He collaborated with Louis Braille, who developed the dot alphabet. One of Pierre Foucault's aims was to enable blind people to communicate in writing with sighted people. In the mid-19th century, he produced a "keyboard-printing machine". This typewriter, made up of thirty levers ending in engraved punches, each operated by a key, made it possible to write in raphigraphy. This typographic system reproduced letters in relief on paper, which could be read both tactilely by blind people and visually by sighted people not trained in the Braille alphabet.

From the United States to France, let's continue our journey to Italy, in the very early days of the 19th century: there we find a blind countess, Carolina Fantoni; the countess's brother, Agostino; and a nobleman - and very gifted mechanic - Pellegrino Turri. According to one version of the story, Agostino invents the first typewriter to help his sister. Turri intervened to improve the tool by adding carbon paper. One version attributes the invention of the first typewriter and carbon paper to Turri alone, who was in love with the Countess. Sixteen letters written on this machine can still be seen in a museum.

Let's go back to the 20th century and introduce Vinton Cerf, who is considered one of the pioneers of the Internet and is also deaf. He played a key role in the development of the first email services, as he explains in an interview with Ability magazine in April 2020. He has had a rich career, working for NASA, ICANN, IBM and Google, among others.

It was at this same company, and at the same time, that another hearing-impaired engineer, Ken Harrenstien, developed a tool to automatically generate subtitles for videos published on YouTube, as reported in the New York Times in November 2009.

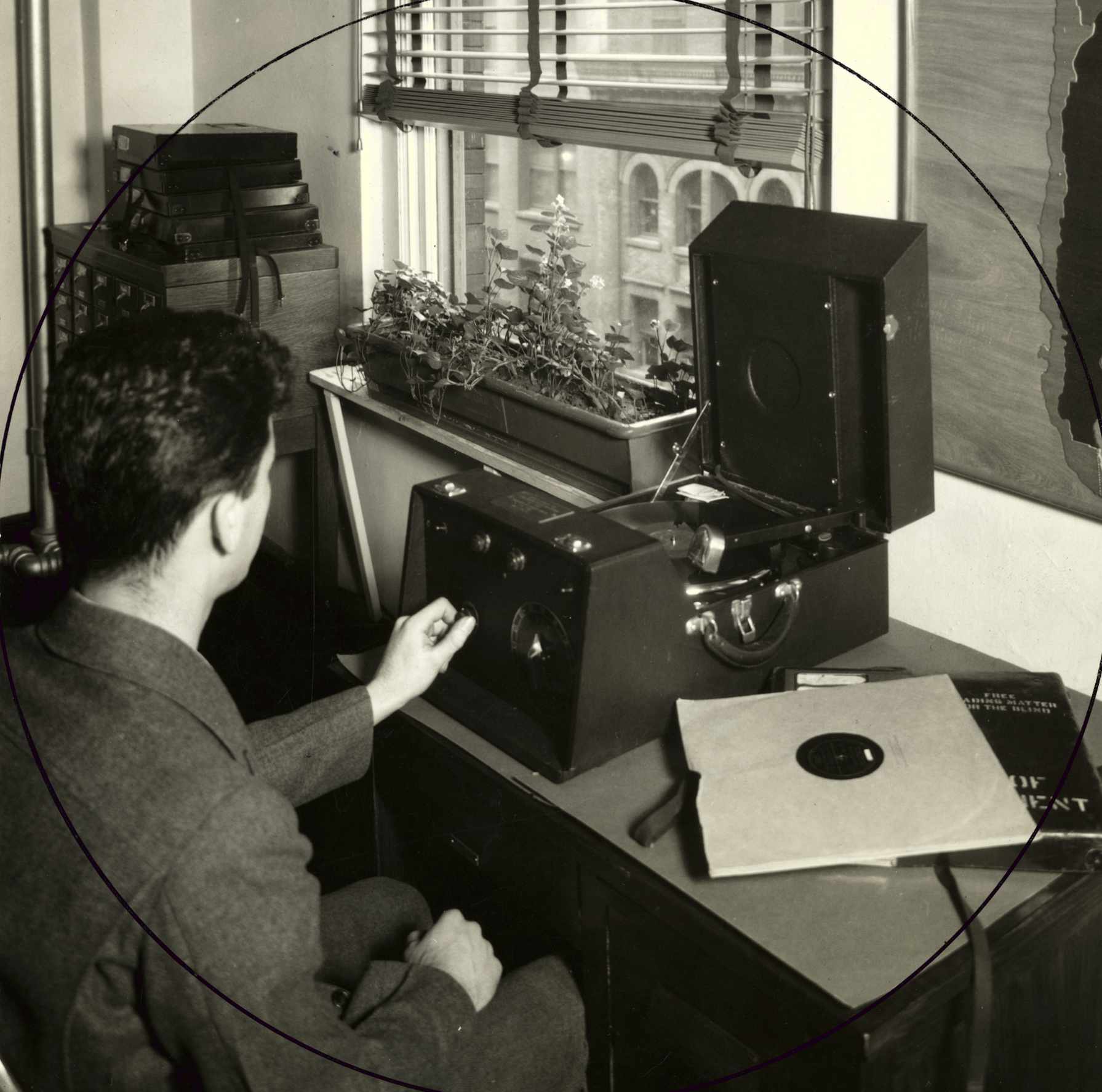

In a widely quoted article, "Disability drives innovations", journalist Shira Ovide asks the question: do you like audio books? "You have the blind to thank for that", she writes, recalling the story of their ancestor, Talking Books, an initiative launched in the 1930s in the United States, when less than 20% of Americans could read Braille. Some visually impaired people had managed to modify their record players so that the story could be told more quickly. Today, the same principle is at work when you want to hear your podcast in an accelerated version.

As for the electric toothbrush, it first appeared in Switzerland in 1954. The Broxodent was originally designed for users with limited motor skills. It has now become an everyday object for everyone.

These examples are by no means exhaustive; they are intended to illustrate a movement, that of inventors who were keen to provide practical solutions to situations of disability. It is not our intention to paint a hagiographic portrait of them, or even to suggest that without them and, more generally, without the world of disability, these innovations would never have seen the light of day. However, they were all the more important in that they represented a major advance, with no alternative, where they later became mainstream objects, providing additional comfort and ease.

Clearly, many products are not always designed with the primary intention of making everyday life easier for people with disabilities. Such is the case with smartphones, which first conquered the general public before incorporating accessibility options. While Apple regularly highlights accessibility as one of the pillars of its developments, the fact remains that Siri, however advanced it may be, is not yet capable of responding to the diverse situations faced by people who have difficulty expressing themselves by voice.

Whether it is at the origin of an innovation or accompanies it, and far from being a brake on creativity, accessibility stimulates innovative approaches. Disabled people are the driving force behind the development of products which, often by changing or reappropriating their use, are also able to meet the needs of the general public.